The "magic word" that gets readers to pay attention

👉 surprising findings about emotional language

I don’t do dinner parties. Probably an early exposure to Abigail’s Party on telly inoculated me.

But if I was playing that game where you say who your dream dinner guests would be then I’m sure one would be Jonah Berger.

Years ago I was fascinated by his research into what made people share things online. Then his work on persuasion - by empathising and removing barriers rather than pushing - rang a lot of bells.

Most of Berger’s research is based around words. Often by analysing large amounts of text, picking out patterns, and seeing how those patterns then affect results. His latest book, Magic Words doubles down on this by looking at how specific types of words can have an outsized impact on your results.

Some of it I’m sure you’ll have heard before. Like the experiment that showed you could cut a photocopier queue by giving a “because” reason - even if that reason was pretty rubbish.

Some of it was new to me but resonated with my experience. For example, using nouns instead of verbs to persuade: touching on identity rather than action. So, for example, you’re much more likely to have success by asking someone to “be a voter” than asking them to vote. Or saying “don’t be a litterbug” rather than “don’t litter”.

But the section I was most interested in was buried in chapter 5 about employing emotion. It was about what grips the attention of an audience. Keeps them reading, watching or listening.

Berger points point that a lot of techniques - like clickbait headlines or gimmicks like celebrity photos in a presentation - can get attention temporarily. But people very soon click away or switch off unless they get something more.

He and his team “analyzed how almost a million people consumed tens of thousands of online articles—not just whether someone clicked on an article but how much of it they read; whether they read the headline and moved on or kept reading for a few paragraphs; whether they skimmed the introduction and left or read the article all the way to the end.”

Obviously, some topics are inherently more interesting than others, so they controlled for that. And they found that even the driest topic can get real engagement depending on how you write about it.

The secret?

Emotional language - but not just any emotional language.

Some emotions got people to give their sustained attention. Others did the opposite.

And it might surprise you to know what worked best.

In his earlier books, Berger pointed out that triggering strong emotions like joy or anger grabbed people’s attention and encouraged them to share articles or videos. But the findings here were very different.

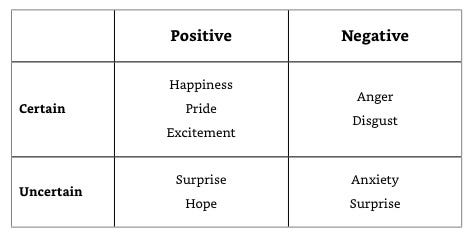

Whether someone paid sustained attention to something wasn’t based on the strength of the emotion or whether it was positive or negative. It was based on the certainty of the language.

Anger, for example, is an emotion of certainty. You know how you feel, you know who is to blame and you want to do something about it.

Anxiety, however, is an emotion of uncertainty. You’re not sure how something will turn out and you’re worried about it. And that means you’re going to pay attention.

Think about the best stories in books and films. If the outcome is certain, there’s no interest. The hero has to be up a tree with rocks being thrown at him. They have to go through ups and downs.

I might watch the highlights of Newcastle vs Villa on Match of the Day to relive the joy of victory. But I’m not paying anywhere near the amount of attention I did when the match was live and it was balanced at 1-1.

Berger’s list of emotions here is far from comprehensive, but I’m sure you get the idea.

If you want sustained attention there has to be uncertainty in what you write and how you write it.

It’s a bit like the point I make about not giving away the punchline of an email or article in your opening paragraph. But applied to your whole article.

Unfortunately, Berger doesn’t expand much on how to do it. There’s a bit more in his co-authored Journal of Marketing research paper, but not a lot.

So there’s a risk here that Berger has just provided evidence for something good writers have always known about - at least subconsciously - without providing any practical steps for implementing it in your own writing.

It’s something I’ll mention to him at that mythical dinner party.

And something I’ll try to help with myself in the next few emails.